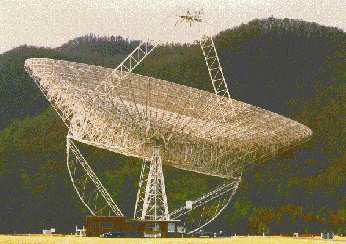

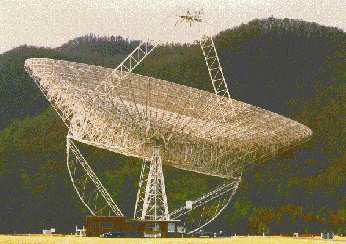

Green Bank and Algonquin Radio Observatories

Michael D. Bicay, Ph.D.

SIRTF Science Center

California Institute of Technology

Pasadena, California USA

One question that is frequently asked by children is: How do you become an

astronomer? Well, there are many paths that can lead to this exciting and

satisfying career. An important element, however, is to obtain a broad-based

education in the physical sciences and in mathematics. In most cases,

professional astronomers have not only attended college but have also gone

onto

graduate school and obtained a doctorate or masters degree. While there are

many fine universities offering degrees in astronomy and astrophysics, I would

urge most young people to consider a broader-based approach. That is, to

obtain training in some combination of physics, mathematics and computer

sciences. With these skills under your belt, you can become an astronomer

with

numerous skills while becoming more attractive to employers if you ever decide

to pursue other interests.

Let me tell you a little more about my experiences. While I had my own small telescope while growing up in Minnesota, my greater interest was in the weather and in becoming a meteorologist. When entering college for the first time, it is not necessary to have a career path mapped out in advance. I enrolled in college at the Eau Claire campus of the University of Wisconsin, with the intention of transferring to the main campus in Madison to study meteorology. And then fate intervened. One of my first-semester professors was an Armenian-American astronomer studying a particular type of galaxy. He immediately drafted me to assist him in his research programs in radio astronomy. Typically, new students concentrate on their academic studies and defer doing research until graduate school or until their last year of undergraduate school. Through hard work and a bit of luck, I was able to participate (and eventually lead) our research investigations. This allowed me to travel to various observatories, including the National Radio Astronomy Observatory facilities in Green Bank, West Virginia and in Socorro, New Mexico.

After graduating with bachelors degrees in physics and in mathematics, I decided to enroll in graduate school. Having been raised in the Upper Midwest, I had seen enough long and cold winters, and therefore had only one requirement when it came to selecting a graduate school: it had to be in California! Fortunately, I was admitted to Stanford University in Palo Alto. Why Stanford?

The University of California in Berkeley was just across San Francisco Bay and is one of the leading astronomy schools in the world. However, I was not (yet) convinced that I wanted to become an astronomer, and I had a variety of interests that I wanted to explore. Therefore, I enrolled in the Applied Physics program at Stanford and took classes in a wide variety of subjects: lasers, optics, cosmology, quantum mechanics, and many others. I decided to apply for a summer student internship at the National Astronomy and Ionosphere Centers Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. I was surprised to hear that I had been selected for one of only three positions. Spending a summer in the Caribbean re-ignited my interest in astronomy. Therefore, I returned to Stanford to complete my coursework and to teach general astronomy for a year. I received an invitation to return to Puerto Rico from my advisor the previous summer, an Italian-American astronomer who was raised in Argentina. I returned to Arecibo and spent the next 30 months conducting research for my doctorate degree. By using the giant Arecibo radio telescope to detect the atomic hydrogen spectral line in galaxies, I began to map the three-dimensional distribution of galaxies in the Universe. This study led to associated research into the properties of spiral galaxies and their dependence on environment.

|

|

Towards the end of my Puerto Rican adventure, I visited NASAs Infrared Processing and Analysis Center (IPAC) at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. This site hosted the data from NASAs first orbiting infrared telescope, the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS). Using radio data that I already had collected at Arecibo, I then added the IRAS infrared data to study the infrared and radio characteristics of galaxies in clusters. Following my 1987 graduation from Stanford, I then accepted a National Research Council appointment at IPAC and studied the infrared and radio properties within spiral galaxies. In attempting to understand some interesting and unexpected results, my colleague in Puerto Rico and I were diverted into studies of cosmic rays and magnetic fields in galaxies. This anecdote wonderfully illustrates the serendipity that appears throughout all of science. One can never predict with certainty the results of science discoveries and their impact on current thinking. The scientific process often leads a researcher down unexpected paths, some of which may result in dead-ends. Such is the beauty and mystery of our Universe and of science itself.

After spending three years at IPAC, I was invited to become a Visiting

Scientist in the Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington,

DC.

This was supposed to be a two-year appointment, but I ended up staying in the

nations capital for six years! This was a considerably different kind of job

than any held before, where managing skills played as large a role (if not

bigger) than my previous science training.

People often asked me what I did at NASA Headquarters. And I could never

formulate a standard answer! The truth of the matter is that I often felt

like

a fire-fighter on the front lines of a major wildfire. While strategic and

long-term planning were an important part of my duties, much of the time was

spent fielding calls from scientists around the country and in dealing with

other offices within NASA -- from the legal office to the procurement

office to

the public affairs office. An important responsibility in serving as a

visiting scientist at NASA Headquarters is to help the agency formulate, with

expert advice from research scientists around the country, and to advocate a

well-balanced space science program that can be conducted within the resources

made available by Congress. Another is to identify and study international

opportunities in which NASA can participate.

After spending three years at IPAC, I was invited to become a Visiting

Scientist in the Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington,

DC.

This was supposed to be a two-year appointment, but I ended up staying in the

nations capital for six years! This was a considerably different kind of job

than any held before, where managing skills played as large a role (if not

bigger) than my previous science training.

People often asked me what I did at NASA Headquarters. And I could never

formulate a standard answer! The truth of the matter is that I often felt

like

a fire-fighter on the front lines of a major wildfire. While strategic and

long-term planning were an important part of my duties, much of the time was

spent fielding calls from scientists around the country and in dealing with

other offices within NASA -- from the legal office to the procurement

office to

the public affairs office. An important responsibility in serving as a

visiting scientist at NASA Headquarters is to help the agency formulate, with

expert advice from research scientists around the country, and to advocate a

well-balanced space science program that can be conducted within the resources

made available by Congress. Another is to identify and study international

opportunities in which NASA can participate.

I look back upon my Washington tenure with great pride and satisfaction in helping to guide various NASA space science programs to reality. Perhaps the most satisfying feeling, however, came to me in an Email from a Nobel Prize winner upon my departure from NASA Headquarters. He thanked me for all of my efforts on behalf of space scientists in the U.S., and stated that he was particularly grateful for working with someone who would find ways to get things done, rather than identify reasons that something could not be done.

I returned to California in late 1996 and joined the science staff of the Jet

Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. While there, I worked in the Project

Office

for the Space Infrared Telescope Facility (SIRTF), the final element in NASAs

Great Observatories program. When completed, this infrared cousin of the

Hubble

Space Telescope will study the Universe at infrared wavelengths. I transferred

to the SIRTF Science Center (SSC) on the campus of the California Institute of

Technology in 1998, where I remain today.

I returned to California in late 1996 and joined the science staff of the Jet

Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. While there, I worked in the Project

Office

for the Space Infrared Telescope Facility (SIRTF), the final element in NASAs

Great Observatories program. When completed, this infrared cousin of the

Hubble

Space Telescope will study the Universe at infrared wavelengths. I transferred

to the SIRTF Science Center (SSC) on the campus of the California Institute of

Technology in 1998, where I remain today.

Most of my time is split between managing two of the divisions within the SSC. The Office of Community Support is the primary top-level interface between the SSC and the astronomers and other scientists who will observe with SIRTF. The Office of Education and Public Outreach is responsible for developing explanatory and educational materials for teachers, students and the general public. It will also be the SSC organization responsible for interfacing with the news media and implementing a public affairs program after SIRTF begins its studies of the cosmos. A small fraction of my time is still devoted to managing some of the NASA programs I was responsible for during my time in Washington.

There you have it one path among many towards becoming an astronomer. Most of my time is now devoted to managerial activities rather than science research. I dearly miss the time spent on mountaintops and in the Puerto Rican countryside, commanding telescopes to study the distant cosmos. On the other hand, I acquired new talents while working at NASA Headquarters, and am now applying those skills as I take on new responsibilities. Fortunately, I am still immersed in astronomy and am able to enjoy a front-row seat to some of the most exciting discoveries that will soon be made!